I cover a ton of miles in this job as Editor of Foster Focus. I’ve driven the Pacific coast from Los Angeles to Seattle. I’ve been through areas of Texas that even Stephen F. Austin hadn’t set foot. I’ve meandered along the same roads that have been featured in films. Stood in the center of the country on a blistering Summer day. I’ve been pretty much everywhere in support of the magazine, creating memories with every mile. The memory that sticks with me most is an afternoon I spent in a small Kansas town.

Concordia, Kansas is a tiny dot on the map of the state but a huge dot on the map of foster care. What makes this sleepy little town such an important landmark in the world of care is both its geographical location and its emotional impact. Concordia sits along the route of the famous orphan trains of the late 1800’s, early 1900’s. Not familiar with the orphan trains? Let’s get you caught up.

The setting is New York City in the 1850’s. The streets are lined with trash, crime and unaccompanied children. There are an estimated 30,000 children wandering the crime-filled streets. Tens of thousands children without parents or supervision. The only known social services are orphan asylums and almshouses, which were homes built by charitable people for the destitute to live in.

With homeless youth and disparity at an epidemic rate, three charitable groups came forward with what they thought was a solution to the problem. Children’s Aid Society, Children’s Village and later the New York Foundlings Hospital began the process of addressing the city’s problem.

The plan was simple, and at a time when media was in its infancy, noncontroversial. CAS and CV would secure homes all across the nation where these forgotten children would be given families that would provide them with a home. They would transport these children to these homes via train, through an arrangement made by Children’s Village and the major train companies. Kids where sent west, dropped off throughout the Midwest to waiting homes.

And there we are. Keep in mind that organized foster care wasn’t really organized until the 1920’s.

For nearly 75 years, 200,000 kids were moved from NYC to little towns all across the country. Let that sink in. 200,000 kids were bathed, dressed in nicer clothes than had ever been worn by these kids, fed and put on a train, on some occasions, with thousands of other kids. The organization is of a “let’s do the best we can” variety, leaving many siblings separated and paperwork lost. Once on the train, endless hours of noisy, bone shaking vibration and the thick smoke bellowing just outside open windows. Sardine packed kids waiting for their stop on the train line.

When the train did finally pull into a station the scene was frantic. Some kids had prearranged families in place. They’d hop off the train and be met with the stern stare of a hard working farm family or the adoring eyes of a couple who longed for a child. Others wouldn’t be so fortunate. To come to town without a gamily in place, children would be paraded before families in the town square. Bulletin and newspaper stories would alert the public to the trains arrival in advance, making for a town square swollen with onlookers and potential parents. The child’s agent, who would be responsible for upwards of 35 children, would present each child to the crowd and finalize any arrangement on site.

And there you go. The train rolls on to the next town. This goes on for almost 75 years!

I knew most of this when I pulled into Concordia, a stop on that ancient route and the current home to the Orphan Train Museum.

In the vein of full disclosure, I’ll admit, that as a product of the system myself, I was pretty angry about the orphan trains. To be pulled so far away from what was considered a little bit like home, was kind of cruel. Auctioning off kids like cars seemed downright criminal. That many kids out in the world with any real supervision or thought about what happens after leaves the train made my chest heart. I’d get a little more clarity after my visit but I definitely went into it with a chip on my shoulder.

I toured the facility with a few friends of mine from Kansas. The first thing Denise Gibson, Daniel Martin, Vicki Richardson and I noticed is the building itself. True to form, the museum rests inside on old train station. It gives you an automatic sense of being there, standing on the planks waiting to hear the whistle that will bring the kids from the big city.

We made our way to the Research Center located just behind the museum, to sign in, pay admission and meet with the Curator of the facility. The Curator is a lovely young woman named Shaley George. After introductions we were taken to a room adjacent to the gift shop to watch a brief video explaining the history of the Orphan Train. We then headed over to the museum.

Walking along a quiet path adorned with statues of children at play we reached the door of the museum. Walking through the door you travel back in time. Carefully maintained hardwood floors meet massive walls that stretch to high ceilings. There are several large rooms filled with archived photos, poster sized stories about life in yesteryear and artifacts of a time forgot. The amount of information that you are presented with right away is staggering. Everywhere you turn is a story, a journey you can take.

Shaley led us through each room. She pointed out various highlights and explained their importance. She’s very knowledgeable about the train, its passengers and the lives they led once they settled in to their new surroundings. It’s quite clear that she has dedicated a great deal of her life to making sure the kids who rode those trains won’t be forgotten. When she finished her explanation of the many exhibits, she stood nearby in case of questions as we all went off in different directions to explore all that the place had to offer.

There were dolls, keepsakes, journals and diaries and photos. Photos EVERYWHERE!

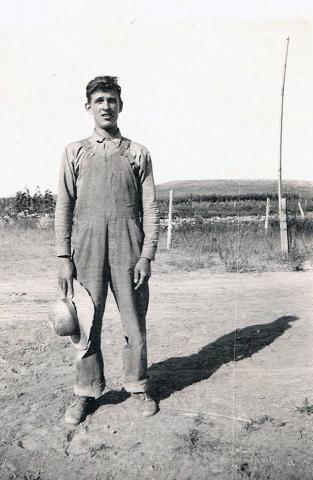

The real power of the Orphan Train Museum is its vast archive. Each step is met with another unique photo, story or memento belonging to a passenger on those trains. The stories and photos are poster sized, making them easy to read and to see the detail in the photos. Photos imposed on curtains over six feet tall cover the windows, giving the room light and a powerful nearly transparent image from the past.

My anger for the process began to go away as I looked at pictures of kids covered in street filth, crammed into tiny rooms with other kids. That’s no way to live. I still resented the way they seemed to be corralled and paraded in front of prospective parents until I began to phathom the enormity that the task of finding homes for that many children at once must have been. Were there faults in the system? Sure, but how different are the challenges of today compared to yesteryear? There is still a huge disparity in the number of homes available for the overwhelming number of kids who need them. It’s still difficult for caseworkers to handle inflated workloads. It’s still tough to know for sure if the home you are sending a child to will be the safest option for them. There are still kids without parents. There are still kids living on the street.

While I still found the methods are archaic, I began to understand the reasoning. That’s what I took away from my visit; a better understanding of why it all happened.

After an hour of exploring (could have been much longer), my group and I made our way back to the Research Center to grab some keepsakes of the visit from the gift shop. I got a cup, an audiobook of Orphan Train stories and some literature about the museum.

Driving away from Concordia, my mind drifted to the faces I’d seen and the stories that accompanied them. 200,000 kids. 200,000 kids taken from a hopeless future to towns all across the nation where they had at least a fighting chance at a normal life. 200,000 kids leaving everything they knew to start life somewhere else. For 75 years, these faces boarded trains West. For 75 years it was the only viable option. Some of those kids held office. Most raised families of their own in the very towns the trains had dropped them. So many kids. So many lives.

A sobering and enlightening visit to Kansas. One everyone involved in foster care should take.

Owner/Editor - Chris Chmielewski

Owner/Editor - Chris Chmielewski