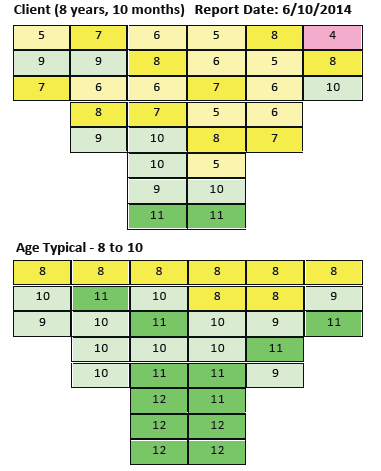

Table 1 (left) represents H’s (Client) brain “map” at the beginning of services. The “map” is a part of the NMT process that approximates developmental capability across 32 functional items like cardiovascular/ANS, temperature regulation/ metabolism, attention/tracking, sleep-sensory integration, attunement/empathy, speech/articulation, reading/verbal, etc. A numerical score is given by the clinician in collaboration with the team for each of the 32 items with 1 being the lowest score and up to 12 being the highest score. When you compare H’s “map” to an age typical map, the effect of H’s developmental experiences is evident.

Table 1 (left) represents H’s (Client) brain “map” at the beginning of services. The “map” is a part of the NMT process that approximates developmental capability across 32 functional items like cardiovascular/ANS, temperature regulation/ metabolism, attention/tracking, sleep-sensory integration, attunement/empathy, speech/articulation, reading/verbal, etc. A numerical score is given by the clinician in collaboration with the team for each of the 32 items with 1 being the lowest score and up to 12 being the highest score. When you compare H’s “map” to an age typical map, the effect of H’s developmental experiences is evident.

SaintA has been committed to implementing the Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics™ (NMT™) since 2008, working closely with Dr. Bruce Perry and the ChildTrauma Academy staff, as well as its NMT™ partners and colleagues. Our journey has been demanding and yet remarkably rewarding, teaching all of us about children, their families and the communities in which they grow up. We have learned a few lessons along the way:

- Trauma is important but not all inclusive. Neglect, relational interactions, neurobiological capability and other developmental opportunities are also very salient

- Resilience is primarily fostered by the strength of a child’s connection to his core groups (family, community, system)

- The capability of parents/caregivers is the most significant variable in child well-being

- The children and families we serve are our best teachers and resources for their own healing

- Hope is indeed possible

H’s story below illustrates the unique perspective that the NMT™ process offers. It is a story of hurt and hope, and how dedication and compassion created opportunities to heal and grow.

H came to his current SaintA treatment foster home after multiple placements and disruptions. This home was H’s fourth foster home, following removal from his birth parent’s custody for the second time. At only seven years old, H had spent the majority of his life in foster care. Throughout his life, H experienced significant adverse events without the buffering of a stable, healthy adult. His parents struggled with mental health disorders diagnosed as schizophrenia and depression, ADOA and their own chaotic/neglectful childhood experiences, all of which impeded their ability to respond to H’s needs and provide an optimal environment for development. In addition, H witnessed domestic violence, experienced the loss of his father’s involvement in his life, homelessness, medical trauma, and several transitions, such as the removal from his family of origin. With this lack of consistency and predictability in his life, H displayed many challenging behaviors when placed with SaintA. These behaviors created significant difficulty in stabilizing and maintaining him safely in the home and community. His diagnoses included ADHD, reactive attachment disorder (RAD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). He was having multiple explosive tantrums each week that involved property destruction as well as verbal and physical aggression. In addition, H had put himself at significant risk for harm, which required the foster parent to provide line-of-sight supervision. If she needed to be away from the home, alternate programming had to be arranged for H, because he was not able to be safely maintained with another adult for periods of more than 30 minutes. H’s biggest triggers appeared to be transitions and intimacy. It was very difficult to prevent H’s tantrums; however, the foster parent had set up the home in a way that allowed H to be safe during the tantrums. He destroyed property with his tantrums, but he had become accustomed to using his bedroom as a more appropriate place to release his physical aggression. The foster mother had developed a process within her home that, to ensure safety, required all other children to leave the area when H started to escalate. H’s explosive behavior also continued to be dangerous when he was in the community. The combination of his intense behaviors (themselves the result of a very sensitized stress response system) and a poorly matched medication regiment from his pediatrician resulted in a hospitalization stay. He had lost 30% of his body weight and was officially labeled with failure to thrive. The team had run the traditional course: individual therapy, medication management, day treatment services, etc. H was very much at risk for a residential stay. The silver lining of H’s hospitalization was that it brought the opportunity for H’s team to re-group and consider a different approach.

Using the NMT™ core principles and H’s NMT™ metric as a guide for understanding the challenges H faced, the team began to create their sequential priorities. The first priority was to figure out how to engage H’s foster parent, recognizing that she was going to be the difference-maker. She committed to a 30-day plan that involved working with an occupational therapist and treatment foster care specialist to enhance H’s regulatory capacity through exposure to a variety of somatosensory activities. Such activities included whole-body activities (riding bikes, playing basketball, swimming); oral activities (chewing gum, blowing bubbles, using a vibrating toothbrush); cognitive and fine motor activities (doing crossword puzzles, building Legos, and playing chess). This process also involved the larger Wraparound Milwaukee team, which included seven formal supports and one informal support— H’s mom. All of these team members agreed to learn all of the regulatory activities and used them during their time with H. Ongoing psycho-education happened with the foster parent, as she started to make the connection between H’s adverse history and the importance of regulation.

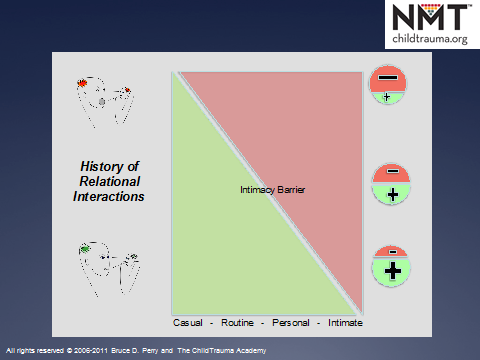

As H started to show small signs of progress, he also began to have moments where he would allow relational interactions to pass through the protective barrier he had erected. This was a remarkable NMT™- related discovery — that some kids have such a high degree of relational sensitivity that the focus must be on enhancing their regulation before attempts are made at relational connection. The foster parent was taught about H’s “intimacy barrier” and learned ways to benefit from his regulatory capacity and interact with him to help him feel safe. These activities were completed the majority of the time in the context of a relationship. At first, the foster mom and other team members conducted the activities in parallel, with H slowly working to close the intimacy barrier. As time went on, the team remained committed to utilizing these activities as a way to reduce negative behaviors and increase H’s ability to appropriately interact with others.

Table 2 (left) represents The Intimacy Barrier. The general premise is that children who have early experiences that are positive, safe & nurturing develop a broader capacity for engaging in interactions that range from casual to intimate and respond accordingly. Children with early experiences that are marked by fear, threat and insecurity often prioritize safety which restricts the risk they are willing to take in the same relational contexts. Like H, these children require patience, repetition and attuned caregiving so that their capacity for more intimate interactions can be gradually enhanced.

Table 2 (left) represents The Intimacy Barrier. The general premise is that children who have early experiences that are positive, safe & nurturing develop a broader capacity for engaging in interactions that range from casual to intimate and respond accordingly. Children with early experiences that are marked by fear, threat and insecurity often prioritize safety which restricts the risk they are willing to take in the same relational contexts. Like H, these children require patience, repetition and attuned caregiving so that their capacity for more intimate interactions can be gradually enhanced.

H’s progress now moved forward at a much quicker pace. H’s stress response system began to experience some much-needed regulation. This resulted in a reduction of the intensity and frequency of his aggressive episodes, from several times a week to once or twice a month. H no longer destroyed property. H began to learn to trust adults and seek out affection. He made improvements with listening to rules both at home and in the community (i.e., previously he had tried to run into the streets or leave the adults he was with, but he was now no longer considered a flight risk). His school also accepted the recommended adaptations, and sensory activities were added to his functional behavioral plan. He was able to successfully discharge from day treatment, remain on a minimal amount of medications and be described as a model student. He stabilized and is now placed with a pre-adoptive family, where he will be able to achieve permanency in several months. H’s story is one of many that are taking place in our community. A group of dedicated foster parents, professionals and teams are learning how to apply core developmental concepts to create hope and healing for the people we serve.

Table 3 (left) represents H’s brain “map” as scored by his clinician and team 18 months later, again compared to an age typical child. Notice the absence of red items compared to his first “map” and also a significant reduction in pink items. These changes suggest that the collective efforts of H’s team contributed to significant gains in developmental capacity, which usually translates to positive changes in behavioral outcomes.

Table 3 (left) represents H’s brain “map” as scored by his clinician and team 18 months later, again compared to an age typical child. Notice the absence of red items compared to his first “map” and also a significant reduction in pink items. These changes suggest that the collective efforts of H’s team contributed to significant gains in developmental capacity, which usually translates to positive changes in behavioral outcomes.

This article is reprinted with permission from the Foster Family-based Treatment Association (FFTA). Originally published in their quarterly newsletter, Focus.

Owner/Editor - Chris Chmielewski

Owner/Editor - Chris Chmielewski